Province scraps plans for Bow River dam near Mînî Thnî

Jessica Lee,

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

The province is pulling the plug on a Bow River dam proposed upstream of Mînî Thnî.

The option is off the table, according to Alberta Environment and Protected Areas, leaving two other sites up for consideration to help prevent flooding in Calgary and bolster water storage for drought management.

In a statement sent to the Outlook, press secretary for Alberta Environment and Protected Areas Ryan Fournier said the province was no longer pursuing the Mînî Thnî dam option.

“We must move forward in a timely manner to prevent floods and mitigate droughts and protect downstream communities and the families who call them home,” he said.

Bearspaw First Nation CEO Rob Shotclose suggested it was unfair to consider flooding Îyârhe Nakoda First Nation lands to begin with and that initial assessments for a dam in the area failed to justify potential impacts.

“This dam would be right in the middle of the Stoney reserve at Mînî Thnî, geographically, and we’ve already been shortchanged land by treaty,” he said. “This would flood over 2,000 acres in the middle of what land we do have in an undisturbed river valley, and we would never get that back. That’s basically sterilizing the middle of the reserve.”

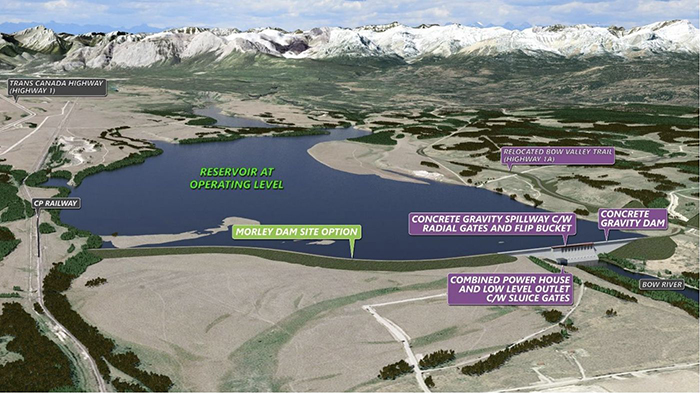

The concrete gravity dam was proposed about 2.5 kilometres west of the Mînî Thnî townsite at a height of 49 metres and would contain a total reservoir volume of 199,100,000 cubic metres (199.1 billion litres), with a maximum reservoir water surface area of 1,025 hectares.

It would require relocating a segment of Highway 1A and about 15 dwellings that would be in the required area for the dam and reservoir.

A March 2020 conceptual assessment of the project site that also considers building a dam between Cochrane and the Bearspaw Dam at the western edge of Calgary and relocating the existing Ghost Dam to expand the Ghost Reservoir, noted there would also be impacts to areas of cultural importance to the Îyârhe Nakoda.

Three previously recorded archaeological sites located in the study area, including prehistoric campsites and stone features could be impacted by the proposed project and would require additional investigation and mitigative studies, the report noted. It was also identified that undiscovered historical resources could be affected.

“There’s a cultural and historical aspect to what a project like this could do to the reserve lands that can’t really be justified, not to mention the environmental aspect,” said Shotclose.

Of the three proposed sites studied, the Mînî Thnî option contains the greatest area of wetlands at 127 hectares, with another 25 hectares within the maximum flood area and an additional 102 hectares within the 1.5 km buffer around the dam site.

The dam facility would be located within the montane natural subregion of the Rocky Mountains, which contains a “diverse and complex mosaic of habitats, which can support a variety of wildlife species,” the report noted.

“Riverbanks; dominated by coniferous stands and occasional deciduous trees, riparian wetlands and shrubbery; provide suitable habitat for a diverse avian community, including grouse, waterfowl, songbirds and owls. The riparian habitat associated with the river corridor attracts ungulates and the rock fields and wetlands adjacent to the river may also provide suitable habitat for reptile and amphibian species. Small mammals, such as chipmunks, voles and shrews, will also use the habitats.”

A grizzly bear zone is also located to the north and south of the study area and identifies the “likely presence of grizzly bear within the study area.”

The purpose of the zone is to avoid development within key habitats and minimize human-bear conflicts and mortalities, however, project effects could include loss of habitat due to forest clearing and disturbance during construction.

To the Îyârhe Nakoda, grizzly bears are revered as a highly spiritual animal, among other species of cultural importance.

“This is one of the most beautiful river valleys, and to be honest, there’s no way that the people would ever accept this project,” said Shotclose, who cited other dam projects pressed on the First Nation.

The Horseshoe Dam, near Seebe, is located on lands acquired from the Îyârhe Nakoda in the early 1900s to provide power to Calgary and the nearby cement plant in Exshaw.

Construction of the Bighorn Dam in 1972, which created Abraham Lake, west of Nordegg and the Goodstoney First Nation reserve of Big Horn, also flooded cabins, pastures and grave sites used by the First Nation, which traditionally hunted and camped in the Kootenay Plains.

The dam, built by the former Calgary Power Company, now TransAlta, proceeded without assessing potential social and environmental impacts or holding any public hearings prior to construction.

“There’s already this precedent when it comes to projects like this that makes it difficult to accept,” said Shotclose. “Internally, the Bearspaw have also had some strong opinions about this new dam project on the Bow River even being studied.”

In June, 2023, Bearspaw First Nation Chief Darcy Dixon penned a letter to Ric McIver, Alberta’s minister of municipal affairs after the minister made premature comments about the dam project in the legislature.

He told the speaker of the Legislative Assembly that a band council resolution had been passed and a blessing was made by Îyârhe Nakoda chiefs and elders at the proposed site of a future dam.

He said the passing of a band council resolution meant “allowing Alberta Environment to do the work.”

McIver asked the former minister in charge of environment, Jason Nixon, to “tell the House how your ministry will shorten the time until we can get an agreement with the Stoney people on where the dam will go.”

“It matters to the Stoney people. It matters to everyone in southern Alberta,” he said.

But Dixon called these statements false.

“I am not aware of any blessings by the Stoney chiefs pertaining to any site of a proposed dam. I know I haven’t provided one,” he wrote at the time. “This mischaracterization gives the false impression we are in favour of the dam project wherein no decision has yet been made.”

The province’s March 2020 conceptual assessment report notes initial meetings took place between the former Alberta Environment and Parks minister with Îyârhe Nakoda First Nation in 2018, before conceptual assessments were held.

It said consultation took place again in March 2019 to share early concepts of the project and to gather initial feedback, as both the Mînî Thnî and Ghost Reservoir options would directly affect the Nation’s reserve lands.

Feedback received then, however, noted the province should look at options that protect Calgary but not cause as much impact to those living outside the city.

Îyârhe Nakoda First Nation further noted it was opposed to all three options proposed. With the relocated Ghost Dam option, there is concern for potential flooding in the Mînî Thnî townsite and overall effects on the Nation’s lands, including erosion of shoreline.

The total project cost for the Mînî Thnî option was estimated at $922 million, including design, construction, land and property purchase, infrastructure relocation and impact mitigation. Cost estimates for the other two options are also in the $900 million range.

The Mînî Thnî cost estimate does not cover additional expenses such as land swaps, compensation payments or agreements for First Nations reserve lands.

According to the province’s website, the feedback process for the Bow River reservoir project is currently in stage two, involving a detailed hydrological study and the possible selection of an option to advance to a third phase.

This round of engagement focuses on the relocated Ghost Dam and Glenbow East options only. A decision from the feasibility study is anticipated by the end of 2024.

“The Relocated Ghost Dam and Glenbow East options have advanced much further and the feasibility studies are nearly complete,” said Fournier “We value the feedback we have received from Albertans on these two options and it will help us decide how best to proceed.

“This includes maintaining an open dialogue with Indigenous organizations and communities who have an interest in the initiative.”

The Outlook reached out to representatives of the Chiniki and Goodstoney First Nations but did not receive a response in time for publication.

Jessica Lee,

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Rocky Mountain Outlook